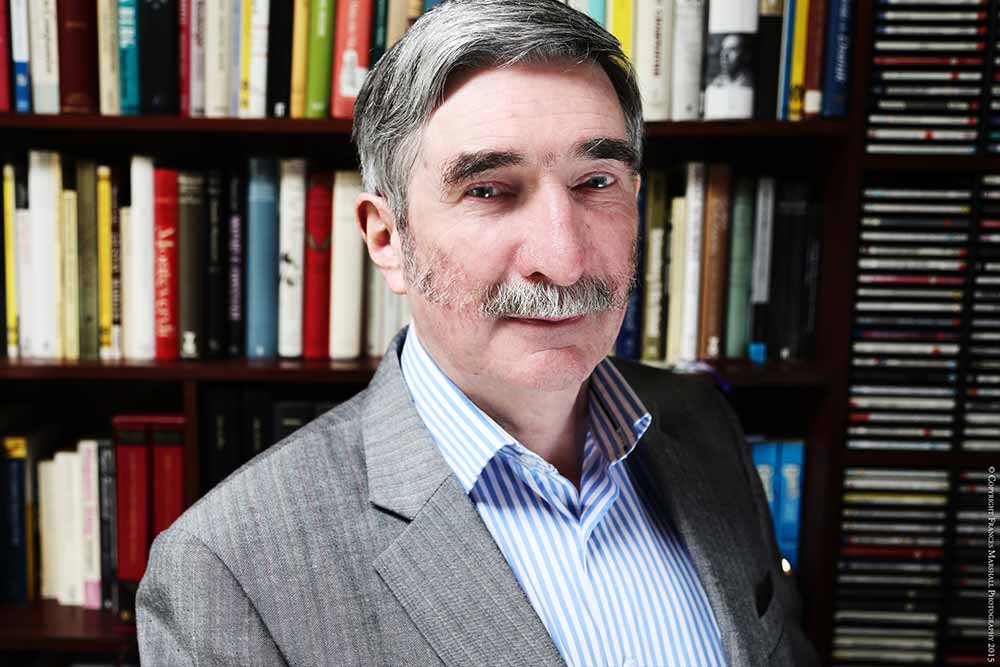

The Score: John Buckley

April 2015

Words by

Emer Nestor

Photos by

Frances Marshall

“My compositions are concerned with movement and stillness; with explosive energy and reflective lyricism; with the play of sound and time”.

— John Buckley

Composer and gifted pedagogue Dr John Buckley is undoubtedly one of the shining lights in the Irish, and indeed the international, realm of contemporary music. His wealth of musical output has found its voice in over fifty countries, with successful premieres in New York, Madrid, Amsterdam, Berlin and London. Both the International Rostrum of Composers, and the International Society for Contemporary Music have featured a selection of his works. In his entry in the Encyclopaedia of Music in Ireland, fellow Irish composer, Martin O’Leary, has attempted to describe the sometimes indescribable — the fearless musical style of John Buckley. For him, the music is underpinned by a ‘broad harmonic idiom’, in which consonance and dissonance coexist within a ‘non-tonal but strongly coloured soundworld’. John is a champion of music education and has played an intricate hermeneutic role in improving the manner in which we teach and understand music in Ireland.

John takes time out from his busy teaching role in St Patrick’s College, Drumcondra to chat about the evolving place of the composer in the Irish Arts scene, and his contribution to this process.

I suggested that there was a need for a summer school for young or emerging composers, or simply for those who had an interest in exploring composition as an option."

How did the ‘Ennis Composition Summer School’ come about, and what was your vision for the project?

I established the Summer School in 1983 in response to an invitation from Mid-West Arts, which was then based in Limerick. The invitation, which was open to all Irish composers, was to devise a project whereby the composer would integrate and become actively involved with music making in the region. Amongst a number of proposals, I suggested that there was a need for a summer school for young or emerging composers, or simply for those who had an interest in exploring composition as an option. There were few places in Ireland at that time, where young composers could study composition. Financial support was provided by the Arts Council, and Coláiste Mhuire, in Ennis. County Clare was chosen as the venue. From the beginning however, the aim was that the summer school should have a national and indeed international profile. My idea for this was influenced, to a considerable extent, by my own experience in attending an international summer school in 1981, given by John Cage and Merce Cunningham at the University of Surrey in Guilford.

The beginning of the ‘Ennis Composition Summer School’ was however more modest, with eight local students of Leaving Certificate standard taking part. The students wrote short musical exercises exploring different twentieth-century styles such as serialism, neo-classicism, minimalism, and so on.

Within a few years the standard of student attending the Summer School had risen considerably, and several of those who subsequently participated went on to acquire distinguished reputations as composers. The duration was extended to 2 weeks and I was joined by other directors, professional guest performers and international guest composers — amongst the latter Peter Michael Hamel from Germany, Karl Aage Rasmussen and Poul Ruders from Denmark, Arne Mellnäs from Sweden, and Paul Paterson, Simon Bainbridge, and Michael Finnissy from Britain.

The summer school, now in its 32nd year, continues to thrive and attract students. Amongst the directors are Martin O’ Leary, Gráinne Mulvey, Nicola LeFanu and Kevin O’ Connell.

Having since evolved to the ‘Irish Composition Summer School’, how does the event meet the needs of aspiring composers today?

I have not been actively involved with the ‘Ennis Composition Summer School’ since 1993, though I have given some guest presentations and of course keep an interest in developments. From speaking to colleagues and students, I know that the school continues to play a vibrant role. Most third-level institutions in Ireland now offer composition as a standard area of study, and many offer it to PhD level. Summer schools can offer something extra with an intense focus and concentration on a single area, with external distraction minimized for a clearly defined period of time. Everything the young composer needs can be found together in one place at one time: professional tuition, professional performers and recording engineers, and equally important, a real opportunity to interact with fellow students. It offers a full immersion in a planned composition project, with a professional recording at the end of the school.

Can you tell us about your association with the publication The Right Note, and the role of music education within the primary school sector.

The Right Note comprises a series of teachers’ manuals, children’s activity books and CD recordings, which provide a resource for the teaching of music in Irish primary schools as outlined in the Primary School Curriculum (1999). The Right Note takes a thematic approach, with one theme per month and all activities for the month fully integrated into the topic. The three musical strands: performing, listening and responding, and composing are resourced with varied and imaginative activities including songs, listening materials, composing activities and a complete programme of musical literacy. There are four sequential stages in the programme: junior and senior infants; first and second class; third and fourth class; fifth and sixth class. The programme was devised and written mainly by staff associated with St Patrick’s College Drumcondra and is published by Folens. Along with colleague Yvonne Higgins, I devised and wrote the third and fourth class materials.

With the acquisition of musical knowledge, skills and concepts, the Primary School Curriculum rightly identifies enjoyment, self-esteem, self-expression and the development of critical judgment to be amongst the aims of music education. When taught well, music in the primary school is intensively active and participatory and affords the child an opportunity to engage creatively and imaginatively. The activities outlined in The Right Note series are intended to provide a practical application of these aims.

As a former primary school teacher what motivated you to move to third-level teaching?

I was a primary school teacher for 11 years between 1971 and 1982. Following this period I worked on a full time basis as a composer until 2001, when I took up a lecturing post in St Patrick’s College, Drumcondra. Throughout my career, I have always composed and have always been involved in teaching and lecturing in parallel. I am deeply committed to both areas and there has never been a time when I wasn’t engaged simultaneously in both.

At various times the focus has shifted from one to the other. From 1971 until 1982, I worked as a primary school teacher in the Holy Spirit Boys National School in Ballymun. By working in the evenings, at weekends and during holidays, I also managed to compose 22 works over this period. These are my first creative endeavours and form the foundation of my compositional output. They include solo instrumental, choral, and chamber compositions as well as 3 works for orchestra. From 1982-2001, my focus was largely on the composition of large-scale works, many for orchestra with peripheral attention to education, though this period did see the establishment of the ‘Ennis Composition Summer School’. Currently, my focus is on academic work in St Patrick’s College, though I have composed over 20 works alongside this. They include 2 concertos for flute and violin respectively.

My decision to accept an academic post in 2001 was based on a variety of factors. At that time I was delivering lectures and educational workshops on a freelance basis for a range of educational and arts bodies to supplement the Aosdána cnuas. The post in St Patrick’s College simply consolidated and focused all this freelance work in one place, though of course it meant giving up the cnuas. A second reason was that I wanted to compose fewer works but of a higher artistic depth and quality. By and large, I feel I have achieved my aims. The college provides a very supportive environment for musical composition. When I retire from academic work in the relatively near future, it is my intention to return to composition on a full-time basis.

I teach melody-writing, harmony and counterpoint, but as standard tonal musical techniques rather than as original composition, so it has no direct bearing on my own compositions."

Does your faculty position at St Patrick’s College, Drumcondra inform your compositional process in any way?

Only in the very broadest sense. While I lecture at Masters level and have supervised PhD students, by far the greatest part of my work in St Patrick’s College is with undergraduate students. I teach melody-writing, harmony and counterpoint, but as standard tonal musical techniques rather than as original composition, so it has no direct bearing on my own compositions.

I also lecture in musicology, currently focusing on the Romantic period. My engagement with the great masterpieces of music history continues to give me inspiration. Amongst the composers are Mendelssohn, Bizet, Brahms, Tchaikovsky and Sibelius. While I have no particular desire to replicate the musical style of Johannes Brahms for example, the manner in which he develops an entire movement from a few small fragments is fascinating and of practical application to my own compositional approach. In similar fashion, the brilliance of Tchaikovsky’s orchestration has had an influence on my own work.

Is there a sense of ‘coming full circle’ as a teacher at your alma mater?

Yes. I took up my lecturing post in St Patrick’s College exactly 30 years after I graduated from there. I now lecture in the same room where I studied music — a room in which I have always felt completely at home. I also organise a regular series of lunchtime concerts there on Wednesdays: approximately 15 each academic year, featuring our music students, invited guests and more recently our ensemble in residence, the Fidelio Trio.

What does it mean to you to be a composer in the twenty-first century?

Creative artists of all disciplines play a vital function in society. The arts are an essential element of civilised society posing questions, inspiration and acting as a counterbalance to consumerism and everyday banality. Artistic expression and engagement are ways of thinking about the world and our place in it. Part of the composer’s function is to contribute to the artistic, cultural and intellectual ferment through creating new compositions. A composer’s role and function remains as it has been throughout history: to compose music. It needs no further justification.

How important is the Contemporary Music Centre and Aosdána in giving a voice/recognition to Irish composers?

Classical music, and in particular contemporary art music, has always had a fragile foothold in Ireland. Its fragmentary and late development in native soil is undoubtedly related to our troubled colonial past, but it is equally true that our independent state has done little to nurture it. The fact that Dublin has had to wait until 1981 for a National Concert Hall, and scandalously still remains without an Opera House, is indicative of the scant interest and support given to music in Ireland.

Ireland’s creative culture is projected nationally and internationally as consisting of the written word and more recently film and rock music. This is evident in every medium of projection including television, newspapers, radio, Arts programmes, advertising tourist guides to Ireland, gala cultural events and so forth. Irish art music and its composers are virtually written out of contemporary culture because of this, and barely register in the public consciousness.

All institutions including CMC and Aosdána, which play a role in supporting Irish composers, are of the utmost importance. They perform a vital function in supporting the individual artist, but equally they give a presence and a sense of solidity to the shadowy existence of Irish composers and composition.

Who do you count among your influences to date?

The list would be extremely long. All the great composers of the past and many lesser ones continue to influence and inspire me for the sort of reasons I have outlined above. Composers in the modernist style have, of course, a more immediate impact on stylistic approaches. Amongst them are Debussy, Bartók, Stravinsky, Lutoslawski, Ligeti, Berio, Dutilleux, Carter — all supreme masters of technical resource placed at the disposal of expressive ends.

How has your style evolved over the years?

My compositional style has undoubtedly changed over the 40 years in which I have been active in the area. My approach now is certainly more assured and refined than in my early compositions. This has evolved gradually rather than displaying sudden dramatic changes of style and direction. At different times I have been preoccupied with different thematic and musical concerns. A number of my compositions during the 1980s for example make significant use of aleatoric techniques, whereas more recent works are concerned with overall formal integration.

Despite these changes in focus, there are abiding concerns in all my compositions. I have always been fascinated by the expressive potential of virtuosity and this remains central to my aesthetic. Musical craft and technical skill are other essential components. Only after mastery of technique is achieved is the composer or performer enabled to be truly expressive. I have grave concerns for art of any genre, music or otherwise, which relies exclusively on idea or concept, but falls short on craft or technical resource.

How important is the collaboration between performer and musical text within your compositional aesthetic?

Collaboration with performers has always played a central role in my work as a composer. I feel very fortunate in having been able to forge lasting artistic relationships with many leading performers both in Ireland and internationally. Almost all my work has been composed for specific performers, ensembles, choirs or orchestras. The performer’s input is invaluable in terms of both technical advice and style of performance, both of which bear a direct influence on the composition. Once the work is complete of course, I am always happy for it to be performed by musicians for whom it wasn’t specifically composed. Each individual or group will bring their own unique energy and performance approach to the work.

As a composer how are you at meeting deadlines?

Extremely good actually — In over 40 years as a composer, I have never missed a single agreed deadline, by as much as a day. On the other hand, I have rarely submitted commissioned works before the deadline. Once a deadline is agreed it is set in stone as far as I am concerned.

Composers depend on musicians and concert organizers to enable their music to be performed. It is a matter of professional etiquette, as well as practicality, to deliver commissioned works by the agreed date.

So many composers, both past and present, have struggled with the psychological aspect of being an artist — how do you achieve mental balance, or is there such a thing?

Musical composition is a highly demanding psychological activity; it is an equally demanding intellectual pursuit. Fortunately, my ideas and concepts for works continue to spring into my imagination — after all, inspiration is everywhere at hand — poetry, nature, mythology, history, other music, personalities of performers and instruments, a new technical instrumental innovation, purely abstract formal designs, the quality of Irish light in late November, a few imagined stray notes — the list seems almost limitless. In addition to this I have worked and continue to work assiduously at refining the craft and technical skill required to develop the ideas into coherent compositions. I find few things in life as demanding as composing and few things as rewarding. If there is such a thing as mental balance it lies somewhere between.

Who would you like to collaborate with in the future?

I would like to continue collaborating with many performers I have already worked with, but I am always open to new artistic avenues. I would like to work with any professional string quartet that might be interested, especially in a series of works. I am delighted to be in collaboration with a number of Estonian performers at the moment, including the kannel player Kristi Mühling and the soprano Arete Teemets. Closer to home, I would like to compose a choral work for the Mornington Singers and a wind quintet for Cassiopeia Winds. I also have a long cherished desire to compose a Concert for Horn and Orchestra for Cormac Ó’hAodáin.

What are you working on at the moment?

I am currently composing a piece for solo chromatic kannel. The ‘kannel’ is the national instrument of Estonia and is closely related to the Finnish kantele, and the Russian gusli amongst other Baltic variants. The chromatic kannel is a twentieth-century development of the traditional instrument giving a range of four octaves. The sonority of the instrument is delicate and atmospheric, characterized by a long lingering resonance.

In the summer of 2014 I wrote a piece Alla Luna for the leading exponent of the kannel, Kristi Mühling and the new piece is also for her. Both works are inspired by and draw their imagery from poetry. Alla Luna draws its title and inspiration from the poem Alla Luna (1819) by Giacomo Leopardi. The poet reflects on the beauty of the moon and the consolation it gives him in his recollection of sadness and trouble in his life. The new piece, for which I don’t yet have a title, is a response to a series of haiku.

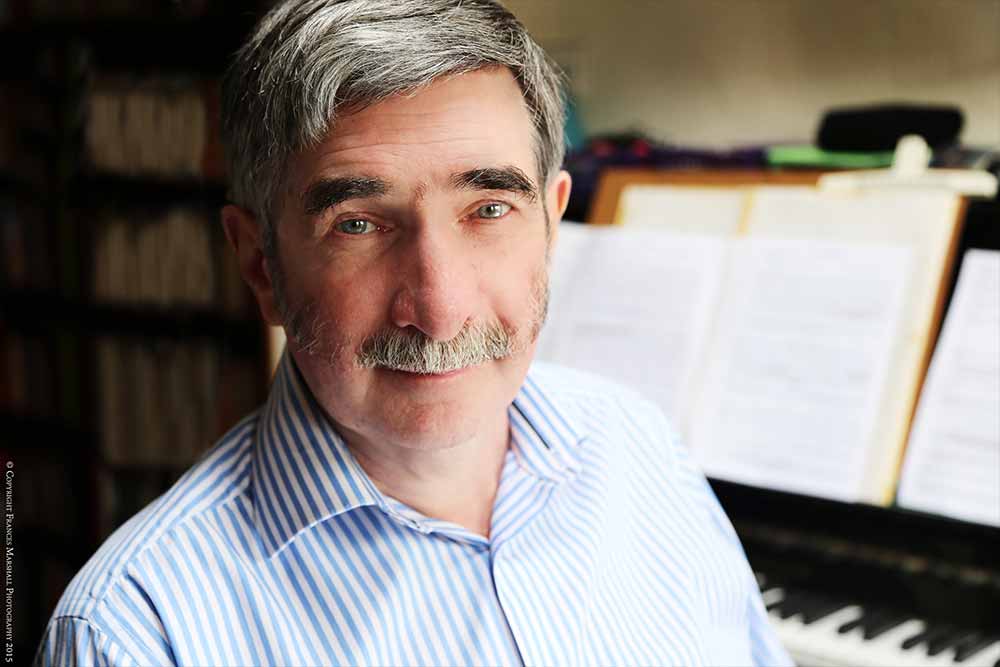

All images displayed in this article are subject to copyright.

Share this article