Telling Stories with Jonathan Dove

November 2018

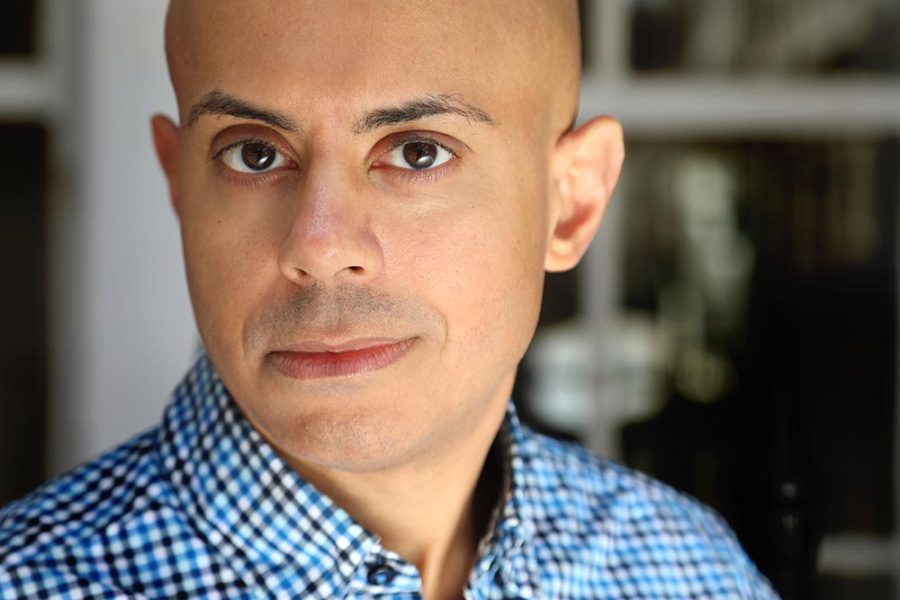

Interview and photos by

Frances Marshall

Share this article

It may seem a little too easy to compare our living artists to deceased legendary figures. However, being compared to Benjamin Britten is a very accurate likening if you’re Jonathan Dove.

Looking at the international success of Jonathan’s works, you have to wonder if there’s a secret recipe to creating art at this level – we discovered that the answer is a profound yes!

We met with Dove in his East London home to talk about how he became one of the world’s most performed contemporary composers, what inspires him on a daily basis and who has helped him along the way.

I needed more objectivity in my composing process: I had to learn to tell when something that was fun for me to play had become boring for an audience to listen to."

You are also regarded as a fine pianist, when did you decide to identify as a composer?

Composing and playing the piano were really the same thing for a long time. As a child, I was always making pieces up at the piano, and I spent my twenties playing in opera rehearsals and accompanying singers in restaurants. When it came to composing, I worked everything out at the piano and writing it down came last. The journey was finding out how to turn the ideas I’d had while I was improvising into a piece that felt finished. I needed more objectivity in my composing process: I had to learn to tell when something that was fun for me to play had become boring for an audience to listen to. 1989 was the year that I could suddenly just work as a composer, there were enough commissions to stop playing the piano for a living, although of course my income plummeted! Nowadays, when I write an opera, I’ll play the whole piece and sing all the parts for the director and conductor or whoever needs to hear it. So playing is always intimately involved.

Tell us about how you became a published composer?

I wrote a piece for Glyndebourne called Figures in the Garden which was one of six wind serenades that they commissioned in 1991 to celebrate Mozart’s bicentenary. It was a high-profile venue, with players from the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, and the other pieces were written by much more established composers: I got the opportunity because one of them didn’t deliver. These six serenades were then recorded by EMI so that made it a viable idea for a publisher. Following on from that, Faber then published some of my choral pieces. Then when I wrote Flight, Edition Peters published it and I moved to them and signed an exclusive agreement.

Tell us about your work with Simon Rattle, when did this begin?

I was 14 when I first encountered Simon, I was playing viola in the London School Symphony Orchestra; we performed Mahler’s Symphony No. 1 and he was only 19, but already a young star. Then two years later he took the orchestra on tour to the United States and we did 18 concerts in 21 days, in 5 states. To play in Carnegie Hall and the Hollywood Bowl among many others was a wonderful experience as a teenager. Also working with Simon was magic. What’s so rare about him is that when I watched him completely, I knew what notes I had to play – you don’t need to look at the music, he gives you everything.

We came to work together again when I was commissioned to write The Monster in the Maze. Simon Rattle has worked with Simon Halsey, his trusted and brilliant chorus master, in the three major orchestras he’s directed. The two Simons were thinking about ways to develop repertoire that would include children. After seeing Britten’s Noah’s Flood with the Berlin Philharmonic I was very inspired. So I wrote The Monster in the Maze along similar lines, but with adults on stage as well children: there are 200-300 amateur performers on stage!

The Monster in the Maze has all the right ingredients to become a regularly performed work – launched by a world-renowned conductor, accessible to all audiences (and yet not dumbed down), performed by both amateurs and professionals together. Why does this mixture work?

Having Sir Simon Rattle conduct the first three productions with the Berlin Philharmonic and the London Symphony Orchestra really launched the piece. It’s gone around the world surprisingly quickly: with performances in German, English, French, Taiwanese, Portuguese, Swedish and Catalan – it’s now my most-translated opera! Also, there has been a big drive from classical music organisations to create works that collaborate with the community, which is necessary and great to see. It’s so important that these institutions look outside of themselves and find new ways of engaging – it’s a way to revitalise the genre.

My greatest inspiration of all is stories of any kind. Paintings tell a story, news events, science – everything can tell a story."

Flight was your first big outing, how has your music developed since then?

Flight is a comedy, and my pieces since then have sounded like the same composer, but I have enabled myself to explore darker themes. I also like to look at new contexts for making opera, so I wrote two operas specifically for television and two for church and cathedral performance. I continued my community interest and wrote operas for family audiences, while also writing an extreme chamber opera that only needs one piano (with 2 players) and 10 singers, so it can be performed in stately homes. I’m always exploring new situations in which opera can happen.

On a daily basis what inspires you?

The career of a composer can be very inward and contemplative, so I try to get out of the flat as much as possible and that’s not for inspiration, more for balance. My greatest inspiration of all is stories of any kind. Paintings tell a story, news events, science – everything can tell a story.

My operas are all stories, and so are many of my other works. Sometimes the stories are only fragments: I just set some parts of Sappho and there’s only one complete poem of hers, the rest are fragments. But they still imply story.

Your music has reached five continents, how have you achieved this?

My first international step came with Flight: I think the fact that I wrote a comic opera, which was practically unheard of in the 20th century, made a connection with its audience and people wanted more. Flight has travelled around the world, and continues to do so: I’ve seen three different productions of it this year. My choral pieces have been performed frequently in America, they travel more in the English-speaking world and areas with a strong choral tradition. Being able to write music that people want to sing is the secret – my music isn’t that easy, but I want the challenges to be fun for the performer, and I don’t want the listener to have to work too hard. I write tunes that people can remember, I use pulse and catchy rhythms and they are not things that you associate with the avant-garde. I don’t like to say my music is accessible, but perhaps audience-friendly.

What’s the secret to writing a comic opera?

A love of theatre is part of it and I’ve spent my life watching plays as well as going to concerts. I love to watch an actor’s sense of timing, hoping to find equivalents of that in music. It does help that I write music with pulse, that makes it easier to deal with comedy. I write diatonic music – it’s harmonically quite transparent and that makes it possible to have complex ensembles, which is also useful in telling a comic story.

Who has influenced your career?

When I graduated and needed to make some money, I rang Jeremy Sams and asked if he had any piano playing work going. He told me to go in and play for the Handel Opera Company the following Monday morning. Little did he know that he was opening the door into opera for me, which completely changed my life. In that rehearsal I was accompanying the countertenor James Bowman and I subsequently went on to write numerous pieces for his voice type in my operas and other works. So Jeremy handed me a whole world of excitement.

David Parry has also been a great champion, who has conducted premieres of many of my operas including the upcoming Marx in London. The composer Stephen Oliver was an important mentor. He sadly passed away at 42, having written 44 operas! He was so special as he also wrote for theatre and showed me that composers can do a lot of different things. Simon Halsey has created many opportunities for me: The Monster and the Maze would have to be the most dramatic. Finally, working with director Graham Vick taught me what opera can be.

I write diatonic music – it’s harmonically quite transparent and that makes it possible to have complex ensembles, which is also useful in telling a comic story."

How do you feel about being constantly compared to Benjamin Britten?

I’m thrilled to even be in the same sentence as Benjamin Britten, he was a trailblazer. He showed that you can write music that’s worth listening to, that combines professionals and amateurs. That children can have a role in opera, that opera can happen without a symphony orchestra or a huge opera house. You can have it in a church, you can have a chamber opera, you can write opera for TV. He wasn’t always the first to do it, but he proved that opera can speak to a large audience in its own time. Whatever I try to do, I find that he got there first and did it better – he showed that it was possible, and I think that’s enormously inspiring.

You’ve set many poems, who are your favourite poets?

There are certain poets that I’ve come back to several times, which is quite telling, and one of them is Emily Dickinson. What I see in her work is a combination of great simplicity on the surface with simple rhyme and regular rhythm, but then enormous depth. There’s a great power to these deceptively simple words which often yield great powerful ideas, so I find her very rewarding to set. Tennyson is a poet I’ve come back to numerous times. He has a great musical discipline so that his rhyme and metre are brilliantly controlled, which is gratifying because he sets up something and maintains it. For a composer, that means you can repeat a melody for different verses if you want to, and it will work.

These are traditional virtues that give you formal elegance and it’s also the case with Vikram Seth, who’s a living poet that I’ve set and we wrote a cycle together. He’s so different from Dickinson and Tennyson, but he’s also very at home with clear rhythm and metre, which I find very idea-making. I’ve worked a lot with Alasdair Middleton who has done many librettos for me – he has a great understanding of what can be sung. When you’re writing something together it’s very different to taking an existing text.

...I get a feeling of how easy a passage is to remember, or how difficult a rhythm might be, which allows me to anticipate the rehearsal process. Everyone can gain from sharing that process."

Tell us about your work with East London schools.

I live in East London, where a lot of my projects have involved the local community, and I’ve written operas just for children. With The Hackney Chronicles and On Spital Fields I was working with groups of 9-year-olds – I would take in the libretto written by Alasdair Middleton, and try out different ways that you could sing one phrase, and then a whole song. We would compose songs as a group and then the children would perform the whole piece. Involving the performers in the composition process gives them a sense of ownership and it helps me to connect with their musical inner life. I may tweak or develop their ideas, but the process helps to guide me and I find it really rewarding. In the workshops, I get a feeling of how easy a passage is to remember, or how difficult a rhythm might be, which allows me to anticipate the rehearsal process. Everyone can gain from sharing that process.

What’s next for you?

I’ve just finished Marx in London and now it’s the moment of truth – it opens in Bonn in December. That’s when I’ll find out if it’s really a comedy!

See More from Jonathan Dove: www.jonathandove.com

All images displayed in this article are subject to copyright.

Share this article