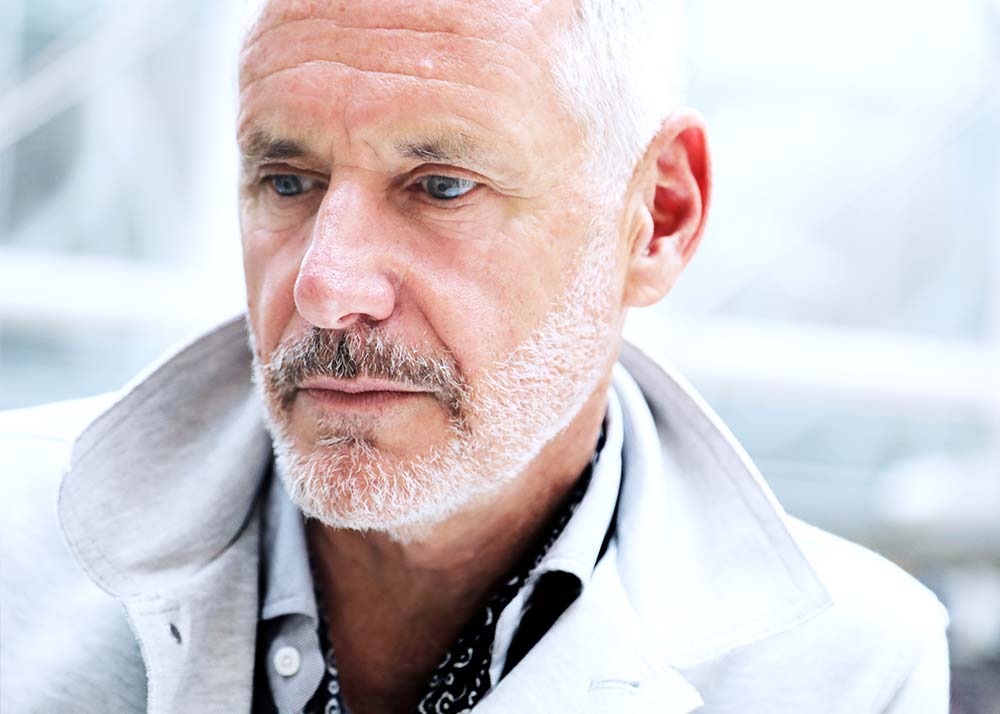

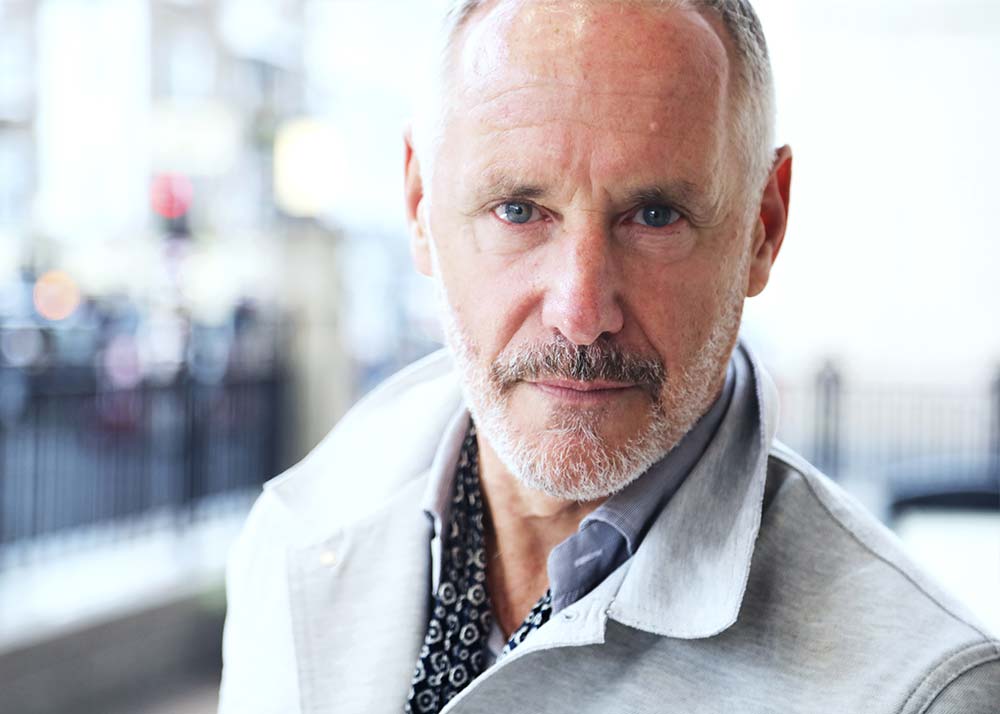

Unifying the Cause with Mark Campbell

June 2019

Interview and photos by

Frances Marshall

Share this article

Easily one of the world’s most in-demand librettists, Pulitzer Prize winner Mark Campbell met with Final Note Magazine in advance of his and composer Iain Bell’s upcoming work Stonewall with New York City Opera to discuss the progress of gay rights, the secrets to his writing process and the importance of honouring yourself as an artist.

I think that opera honours music more than musical theatre does, so I made the jump into opera and haven't really looked back."

When did you decide to become a librettist?

I had been writing lyrics for musical theatre while also holding down a day job and during that time Stephen Sondheim, who remains my greatest inspiration, presented me with the first Kleban Foundation Award and it changed everything for me. Then in 2001, John Musto gave me the job of writing the libretto for the comic opera Volpone, which was a big success at Wolf Trap Opera. All the elements came together and I found my home. I think that opera honours music more than musical theatre does, so I made the jump into opera and haven’t really looked back.

How did the Pulitzer Prize change your career?

My publisher Bill Holab sent me an email about it while I was working at an advertising studio in a windowless room in Long Island City. I yelped when I read it and staff members asked me if I was OK. I was a closeted librettist (laughs), working all day and heading into premiere’s of my pieces in the evening. I was terrified of financial instability and that way of thinking held me back for a long time. It was my husband who said ‘maybe I should take this writing thing more seriously’ (laughs).

It’s extremely important to be told by people more experienced than you that you can do this. Yes it will be scary and a struggle at the beginning, but you must learn to honour yourself as an artist. I was working very hard at my “day job” and putting my focus and energy into all the wrong things. When I decided to devote my full time to writing, my work as a librettist increased massively. I went from writing one opera a year to completing five a year.

Where did your determination to go freelance come from?

My mother was a painter and unfortunately because of her social surroundings and circumstances wasn’t able to be seen as an artist. The role of “mother” was forced upon her and because of this she developed alcohol and drug addictions. She attempted suicide and I grew up in this environment, very aware that this was happening because she wasn’t able to be herself. Every human being needs and deserves to honour who they are – my mother was deprived of this and I had to break the cycle.

Unfortunately, I belong to the generation who lost many friends to AIDS, some being very close. This was a horrendous part of our history and we’re still reeling from it."

Tell us about your upcoming opera Stonewall with New York City Opera.

I would love to say it was my idea (laughs), but the event itself, suggested by NYCO’s Michael Capasso, is all I needed for inspiration. It’s an enormous honour to be involved in this opera because of what this story means to me as a gay man. I also live a few blocks away from the Stonewall Inn and it’s a very special place for me. Unfortunately, I belong to the generation who lost many friends to AIDS, some being very close. This was a horrendous part of our history and we’re still reeling from it.

I still get angry thinking about it. One of my closest friends Ricky died in 1985, two weeks after his diagnosis. His family told people he died from a brain tumour and we weren’t allowed to attend his funeral. It was tragic how many lives were lost, but the way society treated people with the disease is the real tragedy of that time.

The story of Stonewall is still extremely important and needs to be told. It’s about a group of people who united to fight oppression – it’s simple but profound and we’re reaping the benefits of the uprising today. There’s a lot of divisiveness in the LGBTQ+ community and through Stonewall we hope to bring people closer and to remember we’re all fighting the same fight. Working with composer Iain Bell to bring this piece to life has been a dream, he’s a brilliant collaborator.

Do you think that the gay community is very divided by the different generations? You watched your close friends lose their lives to AIDS, for today’s generation that would be quite rare. Are we finding it hard to relate to each other?

Yes, but now it’s so important to come together. Trump is attacking our rights. What he’s doing to transgender rights is nothing more than bullying – there’s no reason for his actions and it’s despicable. He doesn’t value equal rights and there’s currently a movement underfoot in America to take away marriage equality. So the agenda and circumstances are different, but the patterns are the same. The greatest weapon The Right have is invisibility. It’s been proven time and time again, so it’s important to be out. Once someone knows their child, uncle, coworker, husband, wife are members of the LGBTQ+ community, it’s harder to demonise us.

I wanted to write Stonewall because I needed to remind the next generation that their rights were not easily won. The struggle continues and at every step forward there’s an obstacle. The magic of the Stonewall Inn in 1969 was that it was a safe place where people could kiss whoever they wanted, they could dance, flirt and be exactly who they wanted to be. My aim is to get that message across because I owe so much to the uprising. We’ve made enormous strides. Many gay people used to laugh at the idea of marriage – it was so unrealistic that it was considered a joke. Look at us now! Nothing can be taken for granted and uniting is the only way to preserve the progress we’ve made.

How do you connect with a project?

Every project is different. I’ve learned that your unique route into a story is through your heart. You need to ask ‘who/what is your personal connection to this?’. You have to be careful not to go back to your own personal issues every time because then your work will get trapped in a deliberate pattern of confessional art – which isn’t very collaborative. You have to find your own way but also in a way that gives space for others.

A good example would be when I wrote The Shining. In the novel you learn that Jack was abused by his father, this was left out of the movie. So my way into that story was establishing a rather simplistic theme sentence: only a strong love will end generations of child abuse. It’s safe to say that I have complicated relationships with all of my operas (laughs).

Every new project is like a new romance. It begins with a crush — that dizzying time when you objectify the story. But it’s important to hold on to that spark for as long as you can. And if a project drags on for many years, that romance can dwindle and the project will never get off the ground. I tend to get angry when composers don’t respect deadlines because every day that they’re late compromises the project. They’re stealing time from everybody that follows them in the process of creating a new work.

What’s really important to you in your process?

Besides deadlines, if I’m adapting a text of a living author I always want their approval on the text – I’ll actually have it written into my contract. I want them to be happy with how I’ve presented their story.

I’m known for using humour in my work, it creates empathy in an audience and gives them a deeper connection to the story. We’re creating stories for all kinds of people and we’re lifting opera out of the snobbery and pretension that has plagued it for centuries. In the US we’re now seeing opera as a populist artform, isn’t that fantastic?

Every new project is like a new romance. It begins with a crush — that dizzying time when you objectify the story. But it's important to hold on to that spark for as long as you can."

Don't undersell yourself, the industry will undersell you enough."

For upcoming librettists, tell us about the payment structure of the job.

It’s important to talk about money, because it’s such an obstacle for people. The payscale varies a lot and of course there’s budgets that can’t be ignored. But no established librettist should accept anything lower than $50,000 from a major company for an operatic work. Some companies will try to get the price down by saying it’s a shorter work, but short works are actually more difficult to write.

The other big step is not to write a word until the first percentage comes into your bank account. This is a gesture of commitment from the company that’s more psychological than financial. I generally look for three installments, one at commencement, one at completion and one on opening night.

But just as important as money is teaching librettists to get credit for their work. Don’t undersell yourself, the industry will undersell you enough. You must insist on being credited and it should be in your contract. Librettists get ignored all the time and that’s very damaging for the future of emerging writers.

What’s your favourite quote about writing?

That would have to be Annie Dillard’s, and I live by it. It says ‘Write as if you are dying. At the same time assume you write for an audience consisting solely of terminal patients. That is, after all, the case.’ For me that translates to ‘don’t waste anybody’s fucking time’.

To find out more about Mark Campbell see:

www.markcampbellwords.com

For more about New York City Opera’s production of Stonewall:

nycopera.com/stonewall

All images displayed in this article are subject to copyright.

Share this article