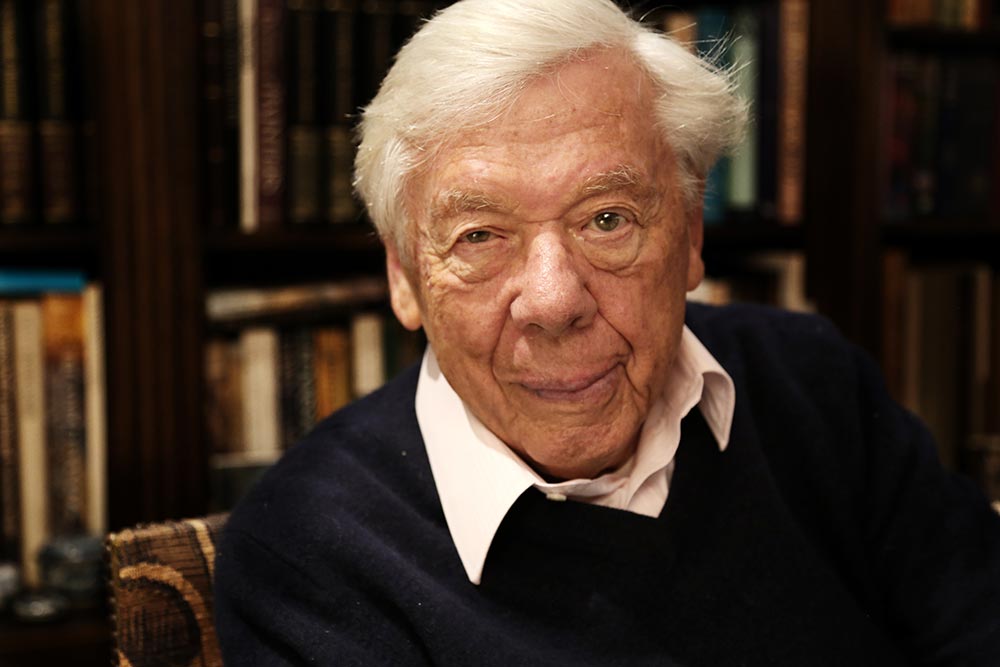

Talking science and music with Sir Ralph Kohn

July 2018

Photos and interview by

Frances Marshall

Edited by

Lesley Bates

Sir Ralph Kohn – leading medical scientist, successful businessman, classical music patron, philanthropist and enthusiastic baritone – gave his last interview to Final Note shortly before his death in 2016, aged 88.

Born in Leipzig, Germany, Sir Ralph Kohn arrived in this country as a penniless refugee in 1940 after fleeing the Nazi regime. He and his family settled in Salford, where he attended Salford Grammar School, before studying for a PhD in pharmacology at the University of Manchester. Post-doctoral studies took him to Rome, where he worked with Nobel prize-winners Ernst Chain and Daniel Bovet, and to the Albert Einstein College in New York.

He left academia for the pharmaceutical industry and in 1969, set up pioneering company Advisory Services, specialising in the clinical assessment of new drugs, and was awarded the Queen’s Award for Export Achievement in 1990. A year later, he founded the charitable Kohn Foundation, which supports research and innovation in science, medicine, arts and education. For 20 years, it sponsored the prestigious Wigmore Hall International Song Competition.

Sir Ralph was elected as an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society in 2006 and knighted in 2010 for services to science, music and charity. As he forged a hugely successful business career, he never forgot his love for music, which began as a child, and he lent financial support to the arts, including the funding of Sir John Eliot Gardiner’s Bach Cantatas project.

Here he shares his enthusiasm for scientific breakthroughs, his pride in his family and his passion for Bach with us.

I think if you want to be a good scientist you must have artistic sentiment and imagination."

You were knighted for your services to science, music and charity, where does your heart really lie?

That’s a very difficult question to answer. I cannot separate the three. If you were to tell me that I could only work in science and medicine, the answer would have to be no. I have another side to me, we all have…. People who are only interested in one particular thing probably do enormously well because they concentrate on the one thing, but I think there’s more to life than just one particular subject. I think if you want to be a good scientist you must have artistic sentiment and imagination. Equally, the great artist has got to be organised and know how he wants to develop his artistry. To become a good musician, there’s also a lot of discipline involved – hours and hours practicing. The brilliance doesn’t come out of nowhere – you need 90% perspiration and 10% inspiration. I feel the great scientist and artist has a healthy proportion of both and they need that to be the complete person.

Do you find there is a strong connection between the scientific and music world and how did it enter your life?

Very much so. Einstein played the violin – some people said he was horrendous, however he played for joy. Apparently, he said it was when some of his loftiest ideas came to him. As a small child, I went to concerts when I was five years old and I started learning the violin when I was six. Music was very much in our Jewish tradition and I was always surrounded by music. It’s only later that I started to develop the voice. My father was very musical and loved vocal music, especially the 19th century Italian repertoire – Verdi, Puccini and so on – but he had a good voice.

You keep your family very close to your working life why is this so important to you?

My family means a tremendous amount to me and we are all very close. My wife Zahava is a Holocaust survivor – she and our eldest daughter Hephzibah travel the world together, talking about her experiences and incarceration in Bergen-Belsen, where she barely survived. They’re wonderful in what they’ve achieved together, talking to thousands of school children, and Zahava was awarded the ‘Freedom of the City of London’ for her services to education. Another daughter, who is an oncologist, does a fantastic job in the area of cancer care and our youngest daughter is a senior Google employee – she has a huge job. The girls are doing well and they’re happy.

All three are married and I have grandchildren. We see a lot of each other, help and support each other and of course it works both ways. Things can never work in one direction: to have a proper relationship with people, it needs to be a two-way effort. You do things for other people, not so you will get something in return, but so that you can share these things. Now this doesn’t mean that we don’t have fierce arguments, but nothing to ever rupture a relationship. Sometimes I want to wring their necks – but then I’m sure they want to do the same to me!

Success is all about being prepared for the right moment. If something doesn’t go the way you expected, find out why… is there a reason far more important than what you set out to do?"

What makes Ralph Kohn get out of bed in the morning?

I am aware that I have a lot of things to do and I do them with great enthusiasm, even though very little of what I do now is to earn a living. Strictly speaking I’m retired, but I’m still heavily involved in scientific, medical and philanthropic matters. I love what I am doing, love meeting people and I have a lot fun in the process. I would like to carry on as long as the good Lord gives me the strength.

Through your career you’ve met and worked with many Nobel prize winners in the field of pharmacology and medicine like Ernst Chain and Daniel Bovet. What makes people achieve such personal success?

Ah, success: there were two famous scientists who defined this. One was Paul Ehrlich, the father of chemotherapy, who said it depends on four factors – ability, money, patience, and luck. Then you have Louis Pasteur who said that chance favours the prepared mind. Take Fleming and penicillin…spores on a petri dish, which most of us would have thrown away. Success is all about being prepared for the right moment. If something doesn’t go the way you expected, find out why… is there a reason far more important than what you set out to do? A lot of discoveries have come about with people thinking that’s a funny a thing, I wonder why. Always keep your eyes and ears open.

You’ve been quite a prominent funder with various projects in music. Why is it so important for you to do this work?

I am still singing. I look after my voice and do all my exercises … I’m very much devoted. It’s 20 years since the Wigmore Hall singing competition started and the Bach Cantata series is now in its tenth year. It’s so wonderful to work with Jonathan Freeman-Attwood and to give these young players this special experience. I’m also one of the main sponsors of Sir John Eliot Gardiner, who had the brilliant idea of doing all the Bach cantatas in the Millennium year all over the world. It was a huge success. I’ve been very fortunate and it gives me great joy.

The Bach programme that you founded in the Royal Academy of Music was a huge success – what drove you to do this and what is your level of involvement?

What drove me was that I believe Bach is the greatest. German Composer Max Reger wrote: “Bach is the beginning and end of all music. Bach has been my greatest inspiration, I owe everything, everything to Bach.” And that is how I feel. To me, Bach’s music is written in heaven – it is the most divine music I know. Bach spent most of his life in Leipzig – where I was born – and this is where he wrote his Christmas oratorio, his B minor mass and most of his cantatas – it’s staggering music. I could live on a diet of Bach. I love Beethoven, Brahms, Schubert etc but if it’s Bach, it’s something so special and unique. I’m an absolute devotee.

Tell us about your company Advisory Services.

The most important thing in drug development is the clinical trial, because we need to know if the drug works. I decided that medical clinical trials were done very badly. The process at the time was slow and slapdash. Industry didn’t have patients and the relationship between doctors in industry and doctors in hospital was very bad. But you have to know the statistics and the tests needed to be controlled and blind. We started the company, Advisory Services, in 1970 – we were independent and could never be accused of being biased, which earned the respect of the top companies in the industry. Within 20 years, we were working for over 100 companies all over the world, and our work earned us the Queen’s Award. So this is where the funds for the Kohn Foundation came from to support science, medicine, the arts (particularly music), humanitarian causes and the Jewish religion along with any other enterprises that we feel compelled to lend support.

What made you want to start the Kohn foundation?

What are you going to do with your life? Sit back and have champagne for breakfast? After I turned 65, I got up the next day and I’ve spent the last 20 years giving money away, being on committees, lending my name to whoever can benefit. Most of the brilliant ideas that happen need money and I want to help.

In relation to the Foundation what is your proudest moment?

When I was made an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society. That was the moment of truth for me. It was a tremendous honour.

All images displayed in this article are subject to copyright.

Share this article