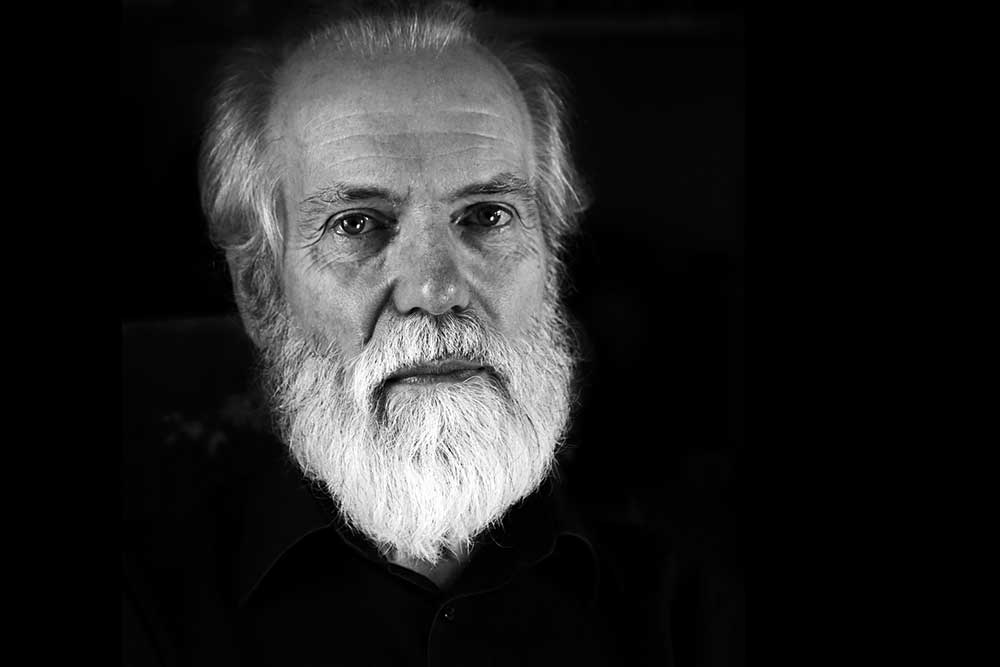

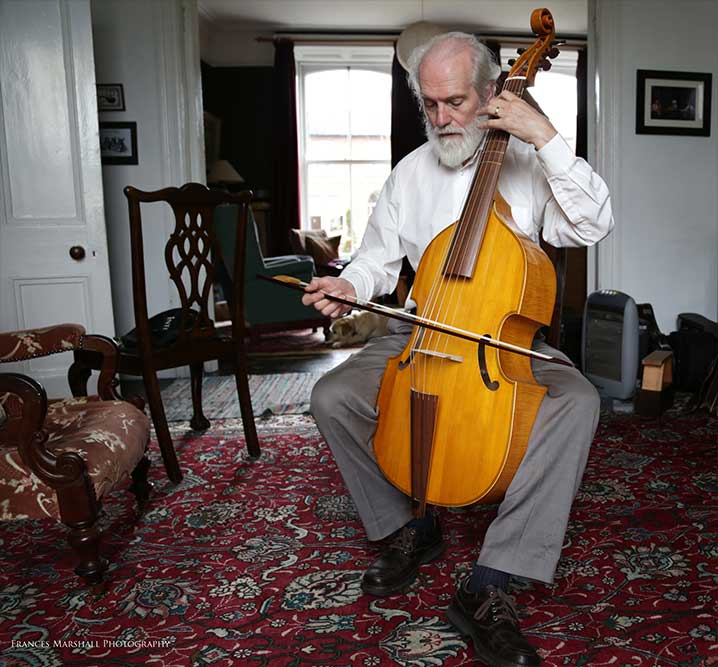

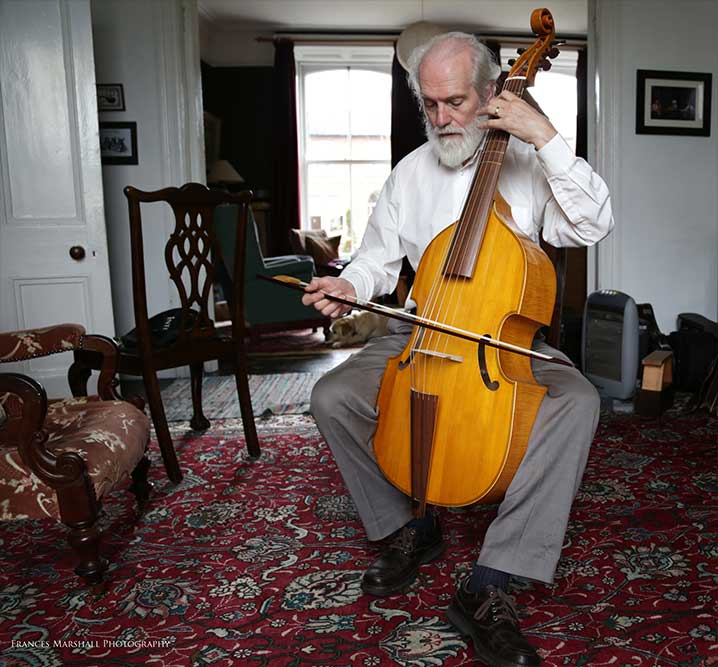

Renaissance Man: Andrew Robinson

May 2015

Words by

Emer Nestor

Photos by

Frances Marshall

Since the late 1960s the name of Andrew Robinson has become synonymous with the Irish Early Music Scene. His inherent passion for this period and natural affinity with its nuances has charmed generations of music lovers. Renowned for his sterling viola da gamba playing, Robinson has performed with the RTÉ Concert Orchestra, the Baroque Orchestra of Ireland and The Irish Chamber Orchestra. He currently teaches at the DIT Conservatory of Music and the Royal Irish Academy of Music.

Robinson shares his thoughts on the value of Early Music and Sol-fa within the university music curriculum, and chats to us about his interest in the world of the Ukulele.

Around the age of 17, I came across a book of sixteenth-century keyboard music and that made more sense to me than the fare of the eighteenth to twentieth centuries."

Why did you decide to pursue an MA in Renaissance Music at Queen’s University Belfast, and what do you remember most from the course?

I took the MA in Renaissance Music because I wanted to study with Ian Woodfield who had written the wonderful Early History of the Viol. Ian was a tremendous lecturer. We were a class of two students, but his preparation and clarity of communication were outstanding — a mighty example to follow.

How did you become interested in playing the viola da gamba?

In my teens I took lessons in the piano, but didn’t relate to much of what I was given to play, however, I got on well with the theory of music. At the same time I picked out chords and songs on the guitar, which gave me grounding in harmony. Around the age of 17, I came across a book of sixteenth-century keyboard music and that made more sense to me than the fare of the eighteenth to twentieth centuries. In my last year of school I went to hear the Dolmetsch family festival of early music in Hazlemere. They were most unattractive and unimpressive — they would walk on stage squabbling like cats, and continue the argument as they walked off — but I picked up a leaflet for the viola da gamba summer school of 1967 and went along. Arnold Dolmetsch’s daughter Nathalie was in charge. She was very much the doyenne; she seemed ancient, although she was actually younger than I am now. She was very kind and welcoming to me.

What do you remember from your lessons with José Vázquez?

José Vázquez was brought by two friends of mine to give a summer school in Dublin in 1979 or so, and I ran Irish summer schools for him throughout the ‘80s. He brought professionalism into the scene, along with great energy and generosity.

Tell us about your work with Barra Boydell back in the days of The Consort of St Sepulchre?

I bought my first viol immediately after my first summer school in 1967. I was 19 and studying music and philosophy in Trinity College, Dublin. There I met Barra, the son of the Professor of Music, and Jenny Groocock, the daughter of my music lecturer. We banded together to provide music for a University Playersproduction of Romeo and Juliet, on recorders, viol, rebec and viola. I transcribed some of the pieces from a record of Renaissance music that I had.

At the same time Jenny and I formed a recorder group, which we called St Sepulchres, after the library (better known today as Marsh’s Library) — I had spent time here cataloguing the viol music of Archbishop Narcissus Marsh at the behest of an English viol player. The two groups amalgamated, with the addition of David Milne and the late Maggie Wilson, following the lead of John Beckett’s London group, Musica Reservata. We then started doing concerts, a great deal of which were held in the TCD Exam Hall. Our first outing, as the interval act for a College Singers concert, was a blast, and we had to do encores!

Jenny and I married in 1969 and Malachy was born in 1970. In his first months he slept in a Moses basket in the wings while we were doing concerts. We lost Maggie Wilson, and Lucienne Purcell took her place as power alto. I had been in a poetry-and-music group with her, called Tara Telephone, where I played the bass viol. When Tara Telephone (also the name of Peter Fallon’s poetry publishing house) split, two members went on to join Horslips. We then took on extra singers and became a ten-piece band.

Lucienne’s husband Fachtna O’Kelly became our manager. He got us onto radio and television, and got a contract from EMI Ireland. We recorded two albums for them in the mid-‘70s, produced by Donal Lunny, and we played warm-up for The Chieftains in the Carlton and in the RDS — Glory days! Then Fachtna went off to manage the Boomtown Rats and Bananarama and other big acts, and we gradually wound down.

As an offshoot of the Consort, why did The Dublin Viols come about?

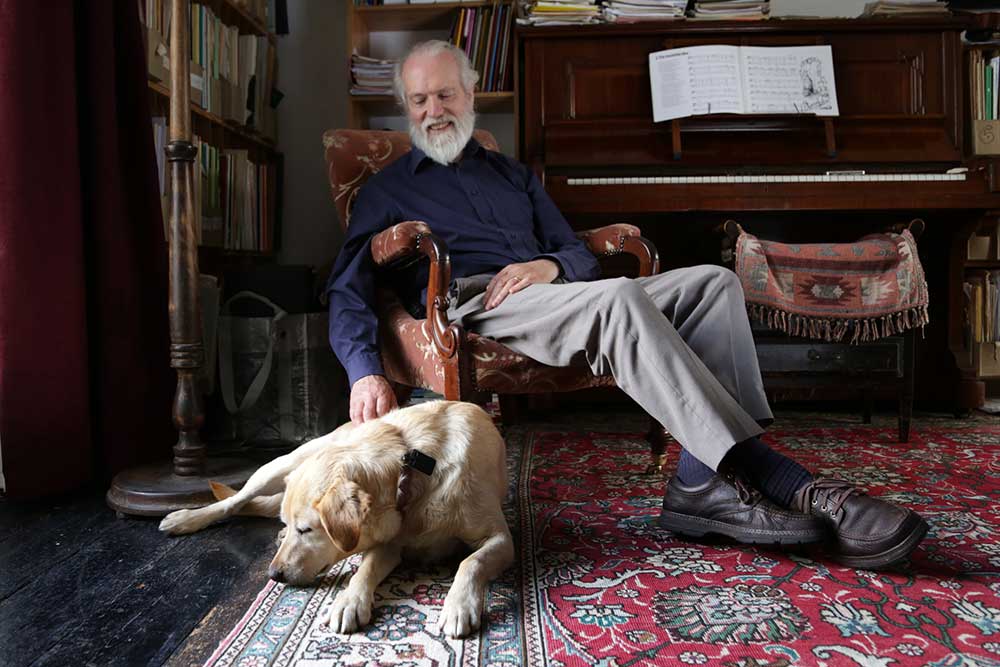

I got a treble and bass viol and persuaded Barra to play the treble (he soon made one for himself). We also persuaded Honor O’Brolcháin, from our original recorder group, to get a tenor and learn to play it. My ambition when I went to the first Dolmetsch summer school was to have a viol consort within ten years. It took a few more than that, but when Barra left Ireland in 1977 to become the world authority on the crumhorn, St Sepulchres closed shop and I went along to John Beckett’s viol consort class and Baroque chamber music class in the Academy. We did several concerts as The Dublin Viols with John leading. That was the kind of enterprise in the 1970s and 1980s where you could often outnumber your audience — but we were relieved, if not encouraged, to hear from Donal Lunny that he had had the same experience in the early days of Sweeney’s Menor The Bothy Band. When John left Dublin again I took over his consort class, and I still run it at home. The Dublin Viols make a few appearances each year, as does our recorders-and-viols group, The Dublin Consort.

What motivated you to build a viol for the RDS Crafts Competition?

After St Sepulchres split up I left my job teaching classical guitar in the Royal Irish Academy of Music and went off for six months to study instrument making in England. At first we made bouzoukis for a short-lived music shop in Ranelagh (Dublin) called ‘The Music Shop’. I subsequently began to make them with my partner and fellow viol player, Anto O Brien. I took lessons in violin repair from the wonderful Willy Hofmann, and Anto took lessons in violin making from a Scottish maker, William Smith. We didn’t make many viols, but we experimented a lot and produced a few good ones.

I also felt at home immediately with the harmony and inventiveness of William Byrd in The Fitzwilliam Virginal Book, which I chanced upon as an uncomfortable teenage piano student."

How were you introduced to Early Music?

I was drawn to a picture of consort playing in a book I had as a child: The Observer’s Guide to Music. It looked like a peaceful, sociable, enlightened thing to be doing, and it is. I also felt at home immediately with the harmony and inventiveness of William Byrd in The Fitzwilliam Virginal Book, which I chanced upon as an uncomfortable teenage piano student. It speaks directly, and it seemed free of a kind of posturing that in those days was painfully associated with classical music by those coming at it from outside. My moral and aesthetic attitudes had been moulded by The Beano (my weekly comic paper), where we learned to buck the system like the Bash Street Kids, and to lampoon, if not quite despise, Lord Snooty and his pals.

What is the place of ‘Early Music’ within the University music curriculum?

It is the foundation of the European musical language. The rules of counterpoint, crystallised in the sixteenth century, are remarkably few and simple, fewer and simpler than the rules of chess. They gave rise to everything that followed, even when the Romantics (especially Berlioz) were rebelling against them. I was enormously lucky, first to learn sol-fa in primary school, then to learn practical harmony by doing pop songs on the guitar, and finally to learn the contrapuntal style of J. S. Bach from Joe Groocock at TCD. That was our entire study, more or less, and I cannot imagine a better grounding in Western music.

As a teacher of Renaissance theory, how do you ‘jazz up’ the mathematics of Counterpoint?

The maths just has to be dealt with, but it’s more like Sudoku than integral calculus. You just have to get into the way of it. I also cover the maths of temperament, which is a topic that arises in Renaissance and Baroque music. For my lecture notes I use an article I wrote on it for the website ‘h2g2’. This site was begun by Douglas Adams when he realised that The Hitch Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (Earth edition) was a thing that the Internet could realize. Life, the Universe, and Everything are dealt with there, in peer-reviewed entries by members. All are welcome to write about whatever they know.

The teaching of Solfège is often overlooked at third-level — what are its benefits?

Sol-fa is really the key to staff notation. Staff notation makes note-spacing look symmetrical in a way that it is not — the steps in a scale are unequal. By naming the degrees of the scale, many of the common problems in reading music are dissolved. I wrote an article on that too for ‘h2g2’, and I use it in my lectures.

Sol-fa is a system of amazing antiquity: it will celebrate its millennium very soon. It was central to music education right through the Middle Ages and Renaissance, and it got a great boost again in the nineteenth century. Kodály (and Joe Groocock) saw its great potential, and it is the basis of the excellent choral tradition in Hungary, and, through Kodály’s influence, many more countries.

As an arranger, how would you define your personal style?

Most of the arranging I do nowadays is putting chords to vintage popular songs for the website ukeireland.com. One of the things that made me uncomfortable with the piano was the way my first teacher dismissed improvisation and playing by ear — things I valued highly as a guitar hitter. I know now that playing by ear is the most important thing to learn. It’s like painting by eye. My pupils seem surprised when I write down the tune and chords of a song on YouTube at first hearing, but every music student should be able to do that. As Joe Groocock taught us, the taking of dictation is the proper aim of music theory lessons. I can write down what you sing just as I can write down what you say, there’s no special talent required for that.

What is the Ukulele scene like in Ireland — why did you take up this instrument?

The ukulele was my first instrument. I found one at home (my eldest brother only told me 50 years later that it was his), and a cousin taught me a few chords and songs. At the age of 10 I moved on to the guitar, and at 19 to the viol. Then in 2009 a man rang my bell at home and asked if I would teach him ukulele. I said “I’d be delighted to.” That was Tony Boland, who organises the Ukeireland website and the annual Ukulele Hooleyfestival (each August in Dún Laoghaire). Tony had been a manager in RTÉ and remembered me from Tara Telephone and St Sepulchres, which had both been on the Late Late Show. The first Hooley was such a success it spawned the Ukulele Festival of Great Britain in Cheltenham. The scene is vibrant and the crack is ninety!

Do you notice an air of snobbery around the instrument, or has its reception changed over the years?

No snobbery, just the odd bit of joshing and blagging. People feel relaxed around the uke, whereas I see anxiety in the faces of young guitarists. The instrument’s small size seems to banish critical expectations. That may not last (it didn’t for the violin after all), but it’s a happy scene for now.

How much fun do you all have in the bands Ukeristic Congress and Aisling Out Walking?

Arising directly from the first Ukulele Hooley in 2009, a group of eight or nine began performing under the name of Ukeristic Congress in February 2010, after which we slimmed down to six, and stayed together for five years. I bought myself a u-bass, an electric bass built on a baritone uke body — the kind of bass the Ukulele Orchestra of Great Britain use. We landed a fortnightly Saturday afternoon residency in Whelan’s front bar — terrific fun and great for our development, which lasted eighteen months. We also found ourselves in demand for weddings, particularly Humanist ones. We were regularly flattered and we loved it.

Aisling Out Walking came about when I heard Aisling Walsh and James Quah singing duets in a Ukeireland monthly pub session. I told them: “You need a bass” and they accepted me. James was also in Ukeristic Congress, and another member, Keith White, has since joined us. James and Keith are amazing uke players, and Aisling (now Mrs Quah) has an irresistible Donegal voice.

What kind of repertoire do you play?

We gravitate towards the old songs: The Springfields’ Island of Dreams was our first three-part harmony number, along with Ruby Murray’s Real Love and other standards of the 1950s and 1960s. We also have a few country songs, such as our signature Walking After Midnight, and older ones like Whispering Hope, and The Devil and the Deep Blue Sea.

Do you see yourself as a philosophical person?

I always had a philosophical bent, and when I came across T. H. Huxley’s essays in a school library I thought to myself: “Evolution changes the perspective on everything; all philosophy and religion needs to be rewritten.” I studied philosophy alongside music at college, and it’s an interest you don’t lose. I came to admire Berkeley and Wittgenstein most of all, but the evolutionary standpoint hadn’t yet made itself felt in Trinity. When I got involved in music I left philosophy to others, though I have provided beginners’ guides to Berkeley and Wittgenstein for ‘h2g2’. Richard Dawkins and Dan Dennett provided the updates I was looking for. Politically, I admire Noam Chomsky.

Do you have any further writing plans?

Not at the moment. I want to produce a publishable score of Henry and William Lawes’s Choice Psalmes (1648), which I edited while doing my MA under Ian Woodfield. Before this however, I have to finish setting up the scores of Beethoven’s Irish song settings, for publication with the original poems replaced by the much better lyrics of Thomas Moore, to the same tunes. The project was the brainchild of the late Tomás Ó Súilleabháin and has subsequently been taken over by his daughter Margaret O’Sullivan Farrell.

How will you be spending the summer months?

We have a few visits planned, with and from the families of our three children. Every year we spend some time in Kerry. I may make a trip or two to Belfast for Ian Woodfield’s monthly viol gathering.

All images displayed in this article are subject to copyright.

Share this article