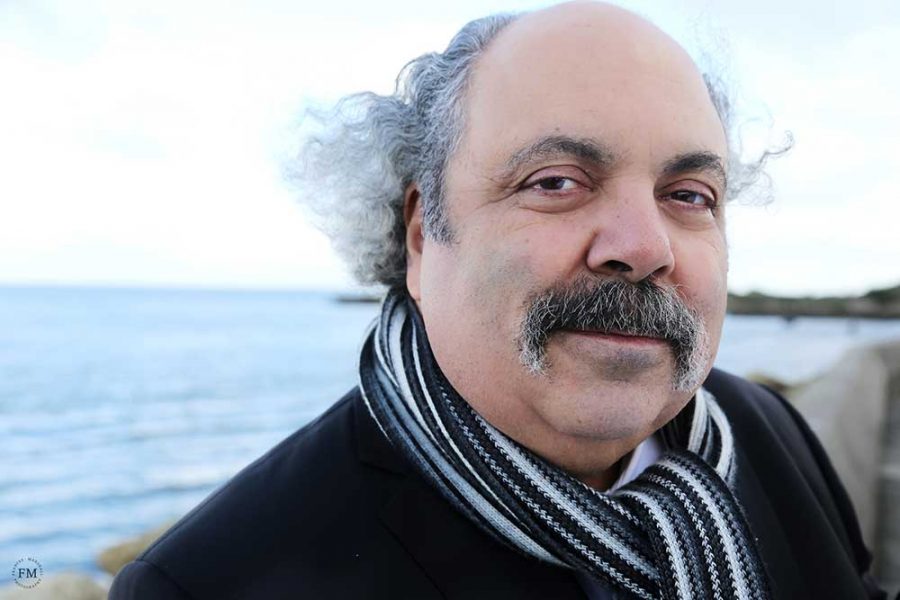

Sound Bites: Brian Masterson

April 2015

Words by

Emer Nestor

Photos by

Frances Marshall

The universally recognized Windmill Lane Recording Studios opened in 1978 with Brian Masterson at its helm.

Dedicated to the production of top-quality Irish and international music, this Dublin-based mecca has played host to a stellar array of artists from across the musical divide since its inception. The walls of this institution have enjoyed the creations of Art Garfunkel, David Bowie, Kylie Minogue, The Fugees, David Gray, Metallica, REM, The Rolling Stones, U2, Norah Jones and Katie Melua, to name but a few. Windmill Lane has also been involved with soundtracks to films such as A Room with a View, My Left Foot, The Field, The Remains of the Day, The Mask, and The Tailor of Panama.

Pioneering sound engineer and producer, Brian Masterson, speaks to us about his time at Windmill Lane, and shares his advice for those hoping to work within the music industry.

The idea of shaping the way the music sounded was very exciting and rewarding. My electronics background was again very useful..."

How did you get into sound engineering and recording?

I played music during college and for some years thereafter. The groups I was part of, Supply Demand and Curve and Jazz Therapy, played mainly in Trinity [Trinity College, Dublin], but also had a loyal following in Galway, Cork and Belfast Universities. We played a strange mixture of progressive free-form jazz and folk. We were definitely a minority interest group of musicians. Myself and my great friend Jolyon Jackson, sadly many years departed, formed the groups and among our members was Roger Doyle, who played drums with us for many years and was part of our ‘Grand Tour of Canada’, which was quite progressive for those days!

As well as playing bass I used my electronics knowledge to build strange Theremin-like synthesizers, which I attempted to play. These were quite primitive and would sometimes take on a mind of their own in the middle of a performance! I was also the one who recorded our demos and I enjoyed that very much. The idea of shaping the way the music sounded was very exciting and rewarding. My electronics background was again very useful, particularly when it came to modifying many disparate components of the recording chain so they would talk to each other. Bit by bit other bands asked me to record tracks for them too. Soon I wanted to be recording as much as playing and eventually, more so.

What inspired you to set up Windmill Lane?

The desire to create a world-class studio in Dublin. It really hurt to see Ireland’s finest musicians and producers having to go to London to make good records. Along with my business partners (James Morris, Russ Russel and Meiert Avis), I decided we should only build and equip a recording studio if we could do it to an extremely high standard. Although the early 1980s were not the easiest time to set up a world class recording studio in Dublin, our decision to aim high was justified, and in 1988 Windmill Lane was voted the Number 1 recording studio in the world by the American Recording Engineer Producer magazine. The list of great Irish and international artists who have recorded at Windmill is extraordinary, and I’m also very happy and proud that many young engineers who started in Windmill have gone on to have very successful careers in the music recording world.

Who have been your musical influences over the years?

They are so many and so varied! My parents were great lovers of classical music and I grew up listening to lots of it, both recorded and occasionally in concert. My Mum sang in 3 Dublin choirs and I would often go to hear them sing or even rehearse. It’s hard to single out particular artists who have influenced me, but along with the great classical composers, I would have to include the music of Joni Mitchell, Miles Davis, Steely Dan, Frank Zappa, Van Morrison, The Beach Boys (Pet Sounds only!) and of course, The Beatles.

Tell us about your work with Irish composer Shaun Davey.

As well as being a very dear friend, I have worked with Shaun and his music for many years. Shaun is probably best known for his ground-breaking Brendan Voyage, but of course there is so much more to his repertoire. Recording Shaun’s music is often somewhat like taking part in a large-scale battle. It’s never simple or straightforward, but always wonderfully stirring and unfailingly melodic. I remember recording The Brendan Voyage in the original Windmill Lane studios. Liam O’Flynn sat in with the orchestra and the whole thing happened there and then — no overdubs. I had known and worked with Liam in Planxty, but I was amazed at how he could play such complex and demanding music with the orchestra. That was a very magical recording session.

I’ve recorded Shaun’s music in football stadiums in the dark with marching pipe bands (The Pilgrim), in the Guild Hall in Derry (The Relief of Derry), in a graveyard in Romania (Voices from the Merry Cemetery), and in a cold little church in Dingle (Béal Tuinne). This will give you some idea of not only the man’s breadth of talent, but also his complete disregard for the comfort of his engineer! In more conventional studio settings I’ve worked with him and the wonderful Rita Connolly on many film and TV scores: Granuaille and his brilliant music for The Special Olympics.

You’ve collaborated extensively with Ireland’s The Chieftains over the years, how did that relationship evolve?

I first worked with Paddy Moloney and The Chieftains soon after Windmill opened its doors. That first recording was actually a 30-second piece of music for a Guinness TV advertisement! Paddy had a reputation for being very demanding about the sound of the group and in fact had recorded previous Chieftain’s albums in London. He and I got on great, he was happy with the sound and he recorded the next Chieftains’ album in Windmill. The last time I counted, I had recorded 28 albums and at least 6 film scores with these amazing musicians. Highlights of my time with The Chieftains include the tour of China in 1983 (when Beijing was actually full of bicycles, not cars and smog). I remember recording the group playing on the Great Wall!

I am a ‘late convert’ to Irish traditional music. I didn’t know much about it in my musician days, but as soon as I started to record bands like The Chieftains, The Bothy Band, Planxty, Altan, Clannad and Stocktons Wing — to name just a few — I began to realise the extraordinary musicianship, feeling and beauty of this music. I’ve never looked back!

For classical recording the goal is to attempt to reproduce the conductor's balance in the control room. It's about faithful reproduction rather than creative construction."

What was it like working with the late Irish tenor, Frank Patterson?

It was a good many years ago of course. Frank normally worked with a wonderful recording engineer colleague — Bill Sommerville Large. Bill couldn’t do some dates and I remember feeling I was a bit of an interloper! Frank was so professional and patient with the whole recording process. Eily O’Grady, his wife, was always on hand to make sure every detail was correct. Classical tenors would not have been my greatest love at the time — but Frank was wonderful, and he had such a great voice. The comparisons with Count john McCormack are well made, I think.

Having recorded a great deal of music by Anúna, how do you set about capturing and balancing their unique sound?

My association with Michael McGlynn and Anúna goes back many years and thankfully, is still going strong. The very first Anúna album was recorded in Blackrock College Chapel, and was then completed with various overdubs in Windmill. It was a bit of a learning curve for both of us! I thought Michael had a very novel way of going about things, but he was so absolutely confident that I didn’t think to question it. He, on the other hand, thought that if I was going along with it, he must be right! It all came good in the end, and we have become great friends and collaborators since then. That first album was a very special event.

Recording Anúna is challenging to say the least. The choir does not perform nor want to sound like classically-trained singers in a conventional choral environment, yet they need to sing in an acoustic that will enhance their performance. We have tried many spaces and places down the years from a studio (which gives me great control but is not the best place for the choir to sing), to lovely old churches, (beautiful acoustic but freezing in winter, and with dogs barking, birds singing and people out mowing their lawns in summer!). The quest continues for that perfect place! If you know of one within an hour of Dublin, please let me know!

My approach to recording Anúna is similar to that of recording classical music. Michael’s compositions and arrangements are so beautiful, complex and often very delicate, that it is a very demanding task to capture them faithfully in a recording. I use a combination of main ambient microphones along with several spot mics that allow for some small changes in balance later. We record a great many takes followed later by lots of very skillful editing to produce the final master. Interestingly, it’s Michael himself who does all the editing — for which I am always most grateful! Editing pure choral music is a black art.

Describe the technical challenges associated with the recording of classical music, as opposed to something more contemporary (or with less musicians).

The first one is finding the right space. Orchestras need a lot of room and they need to perform in an acoustic environment that will enhance the sound they produce. In terms of commercial studios here, Studio One in Windmill Lane is one I know that works. It’s very good, but it’s not a concert hall and so one needs to ‘top up’ the acoustic with some well-chosen reverberation. Studio 1 in the RTÉ radio centre is also a very nice sounding space — it’s larger than Windmill but Windmill has the wonderful Neve console, which is such a beautiful sounding desk.

For classical recording the goal is to attempt to reproduce the conductor’s balance in the control room. It’s about faithful reproduction rather than creative construction. The dynamic range of classical music is very large and therefore very demanding on the excellence of the equipment. But if you’ve got great musicians playing in a beautiful acoustic space and you know where to put your microphones, you’re well on your way to achieving a great classical recording. Of course knowing where to put the microphones is the art!

What are your personal approaches to this kind of recording?

Find a beautiful space. Don’t skimp on the quality of the microphones and pre-amplifiers. Record at high sample rate and bit density. Give yourself some options with a limited number of ‘spot’ microphones. That’s about it! If you can’t have the beautiful space, the others still apply and then you probably need even more microphones and a bit of ingenuity to give yourself enhancement options later on.

Do you have any thoughts on the classical music scene in Ireland at the moment, and our contemporary composers?

The classical music scene in Ireland has always been a difficult place for both musicians and composers. I don’t think we have the ‘critical mass’ in terms of population to make it possible for there to be a good living for all but a few. RTÉ [Ireland’s national public service broadcaster] deserves much praise for their role in keeping alive not only the Symphony and Concert Orchestras, but also the Vanbrugh Quartet, the Philharmonic Choir, and Cór na nÓg. Having worked with many film composers and producers from outside Ireland, it is always wonderful to see their great regard for our orchestral players.

With such an impressive catalogue of filmography behind you, what are your most enduring memories, and what have you learned from the experience?

I’ve been fortunate to work with many great film music composers. If I can single out one person, then the many film scores I worked on with the late Elmer Bernstein were the highlights. I learned so much from Elmer. He would explain to me what he wanted to achieve from each piece, and how the orchestration worked to enhance the emotion on the screen. He had a wonderful way of writing music that worked so well for the picture. He also had the uncanny ability to make changes to the score on the spot at the request of the director. Because he didn’t work with a click track, but watched a sweep hand on a large clock, he could make changes to tempos and content that those locked into a click track just couldn’t manage so easily and seamlessly.

What does the process of score-mixing involve within the creation of a movie soundtrack?

I love recording and mixing music for film. In most cases the music is scored for conventional orchestra but will very often contain other elements, which serve the film. These can be in the form of synth based sounds, extra low frequency material, extra percussion and very often non-orchestral instruments. The music is normally performed to a pre-laid metronome click track. This is to ensure that the music ‘hits’ or coincides with all the right points in the film. No one really likes playing to a click track but it’s part of the deal when you’re recording a film score.

Mixing for film involves awareness of the other elements that pure music doesn’t require. Dialogue is king in film. You need to keep this in mind at all times. Prominent solo musical voices like oboe and clarinet can easily get in the way of speech, so you need to adjust your mix to the presence of dialogue or other sound effects. Also, the low frequency elements and warmth of the music can be lost when music is held low under dialogue — so that can be an issue too.

Sometimes I will be asked to deliver the music mix in stems. These are sub mixes of the total which give the director and film mixer the ability to tailor the music for a specific scene. One might typically deliver stems of strings, brass, woodwind, percussion, solo instruments, choral elements, vocal elements, synth elements etc…

For readers interested in pursuing a career in sound engineering and recording, what advice would you give them?

To record music I think you need creativity, dedication and patience. The hours can be long and the concentration is often intense. I believe that recording music demands considerable musicality from the engineer. The days of the recording engineer in a lab coat keeping a careful eye on the levels are long gone. Recording engineers are now involved as part of the total music team, and when working with rock or pop music, they and the producer play a huge role in actually creating and defining the final sound.

But if you don’t feel music recording is for you there are many other options open, and in fact, many with better employment prospects. Audio post-production in film and television is a big area and requires great skill and talent. Film sound, live music mixing, theatre sound, radio and TV sound, sound for Video Games, Web design etc…

Training in sound used to follow an apprenticeship path. There was little or no formal training available. The situation today is very different. It is worth finding a college that can offer you a good education in your chosen field. This is more important now than ever with the need to hit the ground running in today’s very competitive jobs markets.

What are your plans for 2015?

You know I don’t particularly plan things much nowadays. I love what I do and I’m blessed that many wonderful musicians enjoy working with me. I made so many plans while putting together and running Windmill Lane that now I’m happy to let plans make me!

All images displayed in this article are subject to copyright.

Share this article